Capítulo :

Ilustración de John Ceazon

Sperm whales produce clicking sounds that allow them to view their underwater world with echolocation, a form of sonar. DIY researcher Fabrice Schnöller believes these sounds may also contain a kind of coded language. He built this homemade contraption of surround-sound hydrophones and video cameras to better study sperm whale vocalizations and behavior.Fred Buyle/Nektos.net

The eye of the whale: The sperm whale brain is six times the size of ours and in many ways more complex. It’s the largest brain ever known to have existed, and most researchers believe it allows sperm whales to engage in sophisticated communication. Schnöller and his team hope to be the first to decode what they’re saying.Fred Buyle/Nektos.net

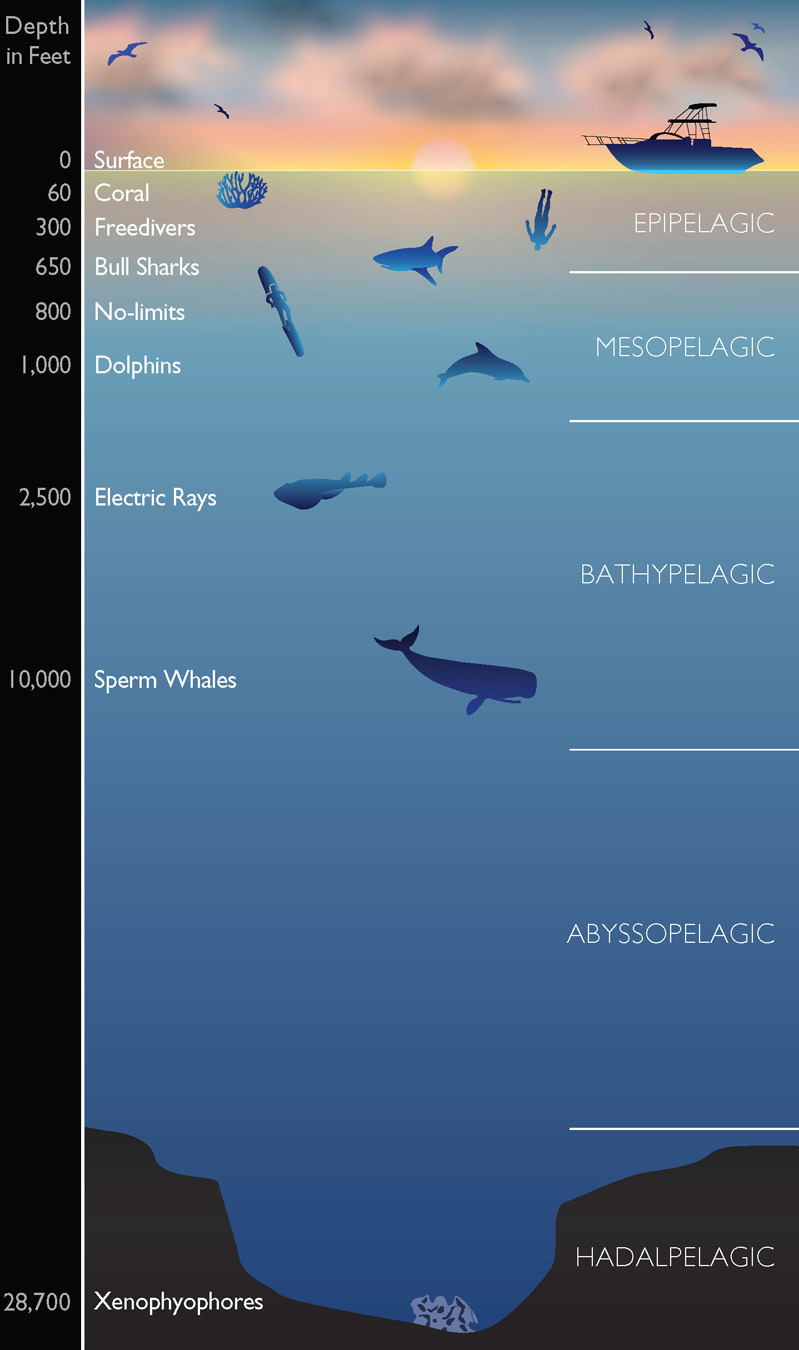

“It’s like being in outer space”: At underwater depths below forty feet, gravity reverses. Instead of floating up, you’re pulled down. Hanli Prinsloo, a champion freediver and ocean conservationist, tries out her deep-water high-wire act.Annelie Pompe/anneliepompe.com

Prinsloo enters a shiver, or group, of blacktip sharks. When freediving researchers approach sharks “on their terms”—that is, deep below the ocean’s surface and without the disruptive gurgle of air bubbles from scuba equipment—the threat of attacks is often negated. The sharks become curious, even docile.Jean-Marie Ghislain/ghislainjm.com

“They’re gentle giants”: Whale sharks are neither whales nor sharks, but the world’s largest fish. They can grow more than forty feet in length and weigh around 50,000 pounds. Prinsloo swims face-to-face with one as it feeds on plankton.Jean-Marie Ghislain/ghislainjm.com

Dolphins “speak” both first names and last names when they approach other dolphins and, sometimes, human freedivers. They may also be able to send one another sonographic pictures, something researchers call “holographic communication.” Schnöller dives down to take a closer listen.Olivier Borde

“Jane Goodall didn’t study apes from a plane”: Of the twenty or so sperm whale scientists who work in the field, none dive with their subjects. Schnöller (center right, with camera) finds this inconceivable. “How do you study sperm whale behavior without seeing them behave, without seeing them communicate?” With his immersive, freediving approach, in five years Schnöller has captured more audio and video footage of sperm whale interactions than anyone before.Fred Buyle/Nektos.net

The key to getting close to whales and dolphins, Schnöller says, is to move in calmly and predictably. With a bit of luck, humpback whales (pictured here), normally very shy, get playful. Sometimes, they approach.Yann Oulia

“They stayed with us for three hours”: A freediver approaches a blue shark in this image captured by Fred Buyle, one of the world’s most sought-after underwater photographers. Buyle aims to document the gentle side of what he calls “the most misunderstood animals on the planet.” An estimated twenty million blue sharks are killed every year for shark fin soup and fishmeal.Fred Buyle/Nektos.net

The human body in its natural form (without weights or wetsuits) is the perfect buoyancy for deep-water diving. We’re able to float at the surface and yet can dive down to great depths while exerting little effort. From left, swimmer Peter Marshall, Hanli Prinsloo, and the author.Jean-Marie Ghislain/ghislainjm.com

As on the moon’s surface, gravity on the seafloor still exists below forty feet but is greatly reduced. Strolling around, doing yoga, even underwater hiking are possible for as long as you can hold your breath. William Winram, a Canadian freediver, takes an amble.Fred Buyle/Nektos.net y williamwinram.com